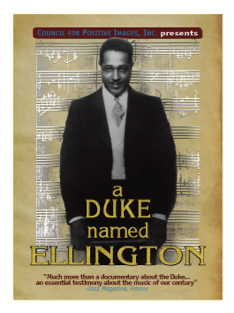

‘A DUKE NAMED ELLINGTON’, the extraordinary, classic two-hour musical biography, makes its debut on DVD in 2007. An ideal tool for jazz research as well as the study of African-American culture, it captures the culturally transcendent genius and charisma of the man and his music, rooted in the Black experience.

Widely acclaimed as the best documentary ever created about one of the world’s greatest musical artists, ‘A DUKE NAMED ELLINGTON’ was nominated in 1988 for an Emmy Award as "Outstanding Informational Special", and garnered international awards.

‘A DUKE NAMED ELLINGTON’ spans half a century, blending previously undiscovered performance footage with recollections of Duke Ellington and his work. Highlights include great solo moments by celebrated virtuosi among the Duke Ellington conglomerate, including saxophonists Johnny Hodges, Paul Gonsalves, Russell Procope, Harry Carney, and Ben Webster; clarinetist Jimmy Hamilton; and trumpeters Cootie Williams and Cat Anderson.

The Duke Ellington phenomenon is poignantly recalled by Herbie Hancock, Charlie Mingus, Ben Webster, Louis Bellson, Clark Terry, Leonard Feather, Herb Jeffries, Jimmy Hamilton, Russell Procope, Teddy Wilson, and others. In rare interviews, the Duke himself recalls his early professional influences and experiences, and reveals his unique method of music-making, his keen sense of humor, and his uncommon philosophy.

It becomes evident, in viewing ‘A DUKE NAMED ELLINGTON’, that not only was Duke Ellington a protagonist in the historical development of American music, blazing a path for other musical artists to follow, but that he continues to provide inspiration for composers, arrangers and musical performers in shaping the future of modern music. The program demonstrates how Duke Ellington contributed to the elevation of jazz from the level of folklore to the realm of music that lives far beyond its time and place.

Widely acclaimed as the best documentary ever created about one of the world’s greatest musical artists, ‘A DUKE NAMED ELLINGTON’ was nominated in 1988 for an Emmy Award as "Outstanding Informational Special", and garnered international awards.

‘A DUKE NAMED ELLINGTON’ spans half a century, blending previously undiscovered performance footage with recollections of Duke Ellington and his work. Highlights include great solo moments by celebrated virtuosi among the Duke Ellington conglomerate, including saxophonists Johnny Hodges, Paul Gonsalves, Russell Procope, Harry Carney, and Ben Webster; clarinetist Jimmy Hamilton; and trumpeters Cootie Williams and Cat Anderson.

The Duke Ellington phenomenon is poignantly recalled by Herbie Hancock, Charlie Mingus, Ben Webster, Louis Bellson, Clark Terry, Leonard Feather, Herb Jeffries, Jimmy Hamilton, Russell Procope, Teddy Wilson, and others. In rare interviews, the Duke himself recalls his early professional influences and experiences, and reveals his unique method of music-making, his keen sense of humor, and his uncommon philosophy.

It becomes evident, in viewing ‘A DUKE NAMED ELLINGTON’, that not only was Duke Ellington a protagonist in the historical development of American music, blazing a path for other musical artists to follow, but that he continues to provide inspiration for composers, arrangers and musical performers in shaping the future of modern music. The program demonstrates how Duke Ellington contributed to the elevation of jazz from the level of folklore to the realm of music that lives far beyond its time and place.

This DVD is no longer in production or available for sale but we have found this link on YouTube and there are some copies available on eBay, etc.

|

|

WHY I MADE THIS FILM - Comment From Terry Carter

I have often been asked what it was that motivated me, an actor, to make this film.

As a youth growing up in Brooklyn, New York in the 1930s and 40s, I had three role models: my father, Paul Robeson, and Duke Ellington. It was essential, particularly in those days, for an African-American child to have positive images with whom to identify and to admire. Wading successfully through the fetid swamp of racism in the America of those days required self-confidence, ambition, indomitability, a thick skin, patience, and above all, optimism about ones ability to survive and prosper. I got all that and more from my idols.

Duke Ellington projected his own special dignity and excellence, eloquently counterbalancing the racist caricatures of African Americans Hollywood was churning out. The awareness that Ellington was up there on the very top helped me to get through those grim, depressing and uncertain days with my head up.

Later, as an actor, I felt a need to become involved in projects meaningful to me, rather than waiting around for the telephone to ring, which is the unfortunate pastime of the majority of actors. So, I took film courses at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Theater, Film, and Television, and set about learning all I could about film production and direction, opened a production office in West Hollywood, formed a corporation, surrounding myself with skilled and experienced co-workers. Among the challenges I faced was my obsession with the idea of creating a film documentary about Duke Ellington that could be a fitting way of repaying a debt of gratitude. That realization turned out to require several years of patient development, archival research and fundraising.

It has proved to be one of the happiest experiences of my entire professional life.

-Terry Carter

a DUKE named ELLINGTON DVD

Council for Positive Images, Inc.

©1988, Council for Positive Images, Inc. All rights reserved

I have often been asked what it was that motivated me, an actor, to make this film.

As a youth growing up in Brooklyn, New York in the 1930s and 40s, I had three role models: my father, Paul Robeson, and Duke Ellington. It was essential, particularly in those days, for an African-American child to have positive images with whom to identify and to admire. Wading successfully through the fetid swamp of racism in the America of those days required self-confidence, ambition, indomitability, a thick skin, patience, and above all, optimism about ones ability to survive and prosper. I got all that and more from my idols.

Duke Ellington projected his own special dignity and excellence, eloquently counterbalancing the racist caricatures of African Americans Hollywood was churning out. The awareness that Ellington was up there on the very top helped me to get through those grim, depressing and uncertain days with my head up.

Later, as an actor, I felt a need to become involved in projects meaningful to me, rather than waiting around for the telephone to ring, which is the unfortunate pastime of the majority of actors. So, I took film courses at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Theater, Film, and Television, and set about learning all I could about film production and direction, opened a production office in West Hollywood, formed a corporation, surrounding myself with skilled and experienced co-workers. Among the challenges I faced was my obsession with the idea of creating a film documentary about Duke Ellington that could be a fitting way of repaying a debt of gratitude. That realization turned out to require several years of patient development, archival research and fundraising.

It has proved to be one of the happiest experiences of my entire professional life.

-Terry Carter

a DUKE named ELLINGTON DVD

Council for Positive Images, Inc.

©1988, Council for Positive Images, Inc. All rights reserved

DUKE ELLINGTON: JAZZ PIONEER FOR 25 YEARS

Duke Ellington - (b. April 29, 1899 - d. May 24, 1974)

There is no better way to describe Edward Kennedy Ellington and his impact on the world of music than to cite this splendid article by Leonard Feather, in 1950:

It was Duke Ellington himself who gave me the idea for this article.

When a man has been as well established in the musical scene as the Duke has this past quarter century, and when so many words of praise have been written about him that every permutation of superlatives seems to have been exhausted, a problem arises.

You know that Duke is still a vitally important figure, yet you find that there is less being written and said about him than about many younger and perhaps less newsworthy entrants into the field.

It was while we were reflecting along these lines that Duke started to muse about some of the advances that have been made in jazz through the years-advances by artists in instrumental and orchestral innovations, as well as by whole bands building new ideas from the production and promotion standpoint.

'Growl' trumpet

The public in general is still inclined to regard Duke mainly as the writer of a string of popular song hits: "Solitude," "Mood Indigo," "Don't Get Around Much Anymore," "I'm Beginning To See The Light," and all the other big factors in his Tin Pan Alley revenue.

However, a survey of his achievements as leader of the world's greatest popular orchestra for more than two decades reveals a remarkable number of "firsts" attributable to the Duke.

Remember when the so-called "growl" trumpet style was a novelty? "Bubber Miley started doing that with us in 1924," reminisces Ellington. "Then later on we had Tricky Sam Nanton doing his trombone solos with a rubber plunger in the bell of his horn."

Those were weird and wonderful sounds back in the '20s, as were the "hot chimes" played by Sonny Greer in Duke's famous "Ring Dem Bells"; the baritone saxophone, seldom previously used, but brought to the forefront by Ellington's Harry Carney; and the small hand drums, now being wildly overworked by the so-called rhumbop and Afro-Cuban groups, first played by Duke himself in 1938 on his own recording of "Pyramid."

Instrumental voice

"Then," says Duke, "I think you can put us down for a first in the wordless vocal department: You hear so much talk nowadays about using the human voice like a musical instrument. I thought that was a pretty good idea in 1927 when Adelaide Hall did it on our original record of 'Creole Love Call.' In fact, I still think it is a good idea, and we use Kay Davis in that style on almost everything she sings with the band nowadays, including the new arrangement of 'Creole Love Call.' Remember 'Transbluency'?" We certainly do. It is one of the loveliest Ellington products of recent years, and no words were required to enable Kay to express the beauty of its melodic line.

In this day and age, of course, the human voice is used as a jazz instrument to an unconscionable degree and the prevalence of bop vocals has given many outsiders the completely distorted idea that bebop consists largely of exuberantly incoherent singing.

Concert jazz

Having played the role of musical pioneer in building so many cornerstones of present-day popular music, Duke might well be expected to have become embittered or cynical about the youngsters who have come up and seized or altered some of his original ideas. Not so. Nearing fifty-one, Ellington is as enthusiastic as ever about young music and musicians, and about incorporating new ideas into his own performances.

The only concessions he makes, in our view, are made in the interests of the somewhat inconsistent demands of commercial expediency. But Duke, like every great bandleader has always had to contend with the battle of art versus commercialism, and has fought it more successfully than many.

"You know," he says, "it's almost twenty years now since we started trying to get away from the limitations of the three-minute form. We were tired of thinking of everything in terms of popular dance music to be made on one side of a record. So in January, 1931, we recorded 'Creole Rhapsody,' which ran on two sides."

Duke invariable uses the regal first person plural when referring to himself, as if the whole band were jointly responsible for everything he has written.

"We did 'Reminiscing In Tempo' in four parts in 1935, 'Crescendo' and Diminuendo In Blue' in 1937, and then the series of long concert pieces."

The concert works marked Duke Ellington's most memorable achievements; though to be fully aware of this it would be necessary for you to have attended every one of the annual Ellington concerts since January, 1943.

"Black, Brown, And Beige," described as Duke's tone parallel to the history of the American Negro, was only recorded in truncated form; the "Perfume Suite" was recorded but never released; "New World A-Coming" was never recorded at all by the band; and the "Liberian Suite" finally came out very recently on a Columbia long playing record.

Rhythmic bass

It was through works like these that Ellington helped to give jazz true stature as concert music, and set the pace for such people as Stan Kenton, who now tries to combine modern classical and jazz influences with an orchestra of almost symphonic dimensions.

The building of a special jazz number around an instrumental soloist, a device used so frequently by Kenton and others today, also owed a great deal of its impetus to Duke, who in 1936 started a series patterned on these lines with "Cootie's Concerto (Echoes of Harlem)," and "Barney's Concerto (Clarinet Lament)."

"Talking about soloists," said Duke, "I think it was our band that popularized the use of the string bass as a rhythm instrument. Around 1927 we helped to establish it in place of the tuba, and then in 1925, when we hired Hayes Alvis and Billy Taylor, we became the first band to use two bass players simultaneously. And, of course, in 1939, there was Blanton. I don't have to tell you about that."

The late Jimmy Blanton was the brilliant young bassist now credited as the originator of an entirely new style and technique, and who made the bass fiddle into a successful medium for melodic solos.

New locations

Duke has never been reluctant to extend his instrumental horizon. If you are one of those who recall the dismay which greeted Cootie Williams' decision to end his long tenure with Duke and join Benny Goodman in 1940, perhaps you also recall how this predicament was turned into an advantage when Duke hired Ray Nance. In addition to his brilliant trumpet work, Nance became the first violinist ever to be featured with the orchestra, and earned himself the nickname of "Floor Show" because of his work as singer, dancer and comedian.

In addition to playing a vital part in determining how jazz was to be played, Duke also lent a helping hand in determining where it could be played. In the early 1930s he pioneered with a tour of DeLuxe Movie Theatres, an avenue of expression previously unknown for the jazz orchestra. Starting in 1925 he broke down a long series of racial barriers that had prevented Negro orchestras from playing any important white locations. In 1933 and again in 1939, he blazed the international concert tour trail, the latter visit including a concert in a bomb-proof Paris shelter. Finally, he established firmly in America that Carnegie Hall and similar auditoriums could be successfully used as a regular outlet for jazz concerts.

What next?

It would be hard to compile a complete list of the Ellington "firsts".

In 1931, he was the first to popularize the word "swing" with "It Don't Mean A Thing If It Ain't Got That Swing," thus paving the way for the swing era. To the throne of which Benny Goodman officially ascended in 1935.

Duke's was the first and only band ever to be voted into the number one position both as the best sweet and the best hot orchestra in the country in the 1946 "Down Beat" poll.

And in case you care, though to use it could hardly seem less important. Duke Ellington used the technique of standing at the piano during his stage shows many years before Maurice Rocco and other vertical keyboard technicians thus identified themselves.

This is the record of Ellington's past. Where does he go from here?

Last year, the same "Down Beat" that had accorded him so may poll victories came out with a sensational attack, declaring that Ellington was washed up, that his band was a shambles, and he might as well disband it before it fell apart beneath him.

That it was a sensational attack and that it hurt Duke personally as well as damaging his prestige and bookings, is indisputable; and there have been many times when even the most rabid Ellington fans have felt this way about the Duke.

http://www.leonardfeather.com/feather_ellington.html

(Editor’s note: This was written and published six years before the spectacular Ellington renaissance at Newport!)

Duke Ellington - (b. April 29, 1899 - d. May 24, 1974)

There is no better way to describe Edward Kennedy Ellington and his impact on the world of music than to cite this splendid article by Leonard Feather, in 1950:

It was Duke Ellington himself who gave me the idea for this article.

When a man has been as well established in the musical scene as the Duke has this past quarter century, and when so many words of praise have been written about him that every permutation of superlatives seems to have been exhausted, a problem arises.

You know that Duke is still a vitally important figure, yet you find that there is less being written and said about him than about many younger and perhaps less newsworthy entrants into the field.

It was while we were reflecting along these lines that Duke started to muse about some of the advances that have been made in jazz through the years-advances by artists in instrumental and orchestral innovations, as well as by whole bands building new ideas from the production and promotion standpoint.

'Growl' trumpet

The public in general is still inclined to regard Duke mainly as the writer of a string of popular song hits: "Solitude," "Mood Indigo," "Don't Get Around Much Anymore," "I'm Beginning To See The Light," and all the other big factors in his Tin Pan Alley revenue.

However, a survey of his achievements as leader of the world's greatest popular orchestra for more than two decades reveals a remarkable number of "firsts" attributable to the Duke.

Remember when the so-called "growl" trumpet style was a novelty? "Bubber Miley started doing that with us in 1924," reminisces Ellington. "Then later on we had Tricky Sam Nanton doing his trombone solos with a rubber plunger in the bell of his horn."

Those were weird and wonderful sounds back in the '20s, as were the "hot chimes" played by Sonny Greer in Duke's famous "Ring Dem Bells"; the baritone saxophone, seldom previously used, but brought to the forefront by Ellington's Harry Carney; and the small hand drums, now being wildly overworked by the so-called rhumbop and Afro-Cuban groups, first played by Duke himself in 1938 on his own recording of "Pyramid."

Instrumental voice

"Then," says Duke, "I think you can put us down for a first in the wordless vocal department: You hear so much talk nowadays about using the human voice like a musical instrument. I thought that was a pretty good idea in 1927 when Adelaide Hall did it on our original record of 'Creole Love Call.' In fact, I still think it is a good idea, and we use Kay Davis in that style on almost everything she sings with the band nowadays, including the new arrangement of 'Creole Love Call.' Remember 'Transbluency'?" We certainly do. It is one of the loveliest Ellington products of recent years, and no words were required to enable Kay to express the beauty of its melodic line.

In this day and age, of course, the human voice is used as a jazz instrument to an unconscionable degree and the prevalence of bop vocals has given many outsiders the completely distorted idea that bebop consists largely of exuberantly incoherent singing.

Concert jazz

Having played the role of musical pioneer in building so many cornerstones of present-day popular music, Duke might well be expected to have become embittered or cynical about the youngsters who have come up and seized or altered some of his original ideas. Not so. Nearing fifty-one, Ellington is as enthusiastic as ever about young music and musicians, and about incorporating new ideas into his own performances.

The only concessions he makes, in our view, are made in the interests of the somewhat inconsistent demands of commercial expediency. But Duke, like every great bandleader has always had to contend with the battle of art versus commercialism, and has fought it more successfully than many.

"You know," he says, "it's almost twenty years now since we started trying to get away from the limitations of the three-minute form. We were tired of thinking of everything in terms of popular dance music to be made on one side of a record. So in January, 1931, we recorded 'Creole Rhapsody,' which ran on two sides."

Duke invariable uses the regal first person plural when referring to himself, as if the whole band were jointly responsible for everything he has written.

"We did 'Reminiscing In Tempo' in four parts in 1935, 'Crescendo' and Diminuendo In Blue' in 1937, and then the series of long concert pieces."

The concert works marked Duke Ellington's most memorable achievements; though to be fully aware of this it would be necessary for you to have attended every one of the annual Ellington concerts since January, 1943.

"Black, Brown, And Beige," described as Duke's tone parallel to the history of the American Negro, was only recorded in truncated form; the "Perfume Suite" was recorded but never released; "New World A-Coming" was never recorded at all by the band; and the "Liberian Suite" finally came out very recently on a Columbia long playing record.

Rhythmic bass

It was through works like these that Ellington helped to give jazz true stature as concert music, and set the pace for such people as Stan Kenton, who now tries to combine modern classical and jazz influences with an orchestra of almost symphonic dimensions.

The building of a special jazz number around an instrumental soloist, a device used so frequently by Kenton and others today, also owed a great deal of its impetus to Duke, who in 1936 started a series patterned on these lines with "Cootie's Concerto (Echoes of Harlem)," and "Barney's Concerto (Clarinet Lament)."

"Talking about soloists," said Duke, "I think it was our band that popularized the use of the string bass as a rhythm instrument. Around 1927 we helped to establish it in place of the tuba, and then in 1925, when we hired Hayes Alvis and Billy Taylor, we became the first band to use two bass players simultaneously. And, of course, in 1939, there was Blanton. I don't have to tell you about that."

The late Jimmy Blanton was the brilliant young bassist now credited as the originator of an entirely new style and technique, and who made the bass fiddle into a successful medium for melodic solos.

New locations

Duke has never been reluctant to extend his instrumental horizon. If you are one of those who recall the dismay which greeted Cootie Williams' decision to end his long tenure with Duke and join Benny Goodman in 1940, perhaps you also recall how this predicament was turned into an advantage when Duke hired Ray Nance. In addition to his brilliant trumpet work, Nance became the first violinist ever to be featured with the orchestra, and earned himself the nickname of "Floor Show" because of his work as singer, dancer and comedian.

In addition to playing a vital part in determining how jazz was to be played, Duke also lent a helping hand in determining where it could be played. In the early 1930s he pioneered with a tour of DeLuxe Movie Theatres, an avenue of expression previously unknown for the jazz orchestra. Starting in 1925 he broke down a long series of racial barriers that had prevented Negro orchestras from playing any important white locations. In 1933 and again in 1939, he blazed the international concert tour trail, the latter visit including a concert in a bomb-proof Paris shelter. Finally, he established firmly in America that Carnegie Hall and similar auditoriums could be successfully used as a regular outlet for jazz concerts.

What next?

It would be hard to compile a complete list of the Ellington "firsts".

In 1931, he was the first to popularize the word "swing" with "It Don't Mean A Thing If It Ain't Got That Swing," thus paving the way for the swing era. To the throne of which Benny Goodman officially ascended in 1935.

Duke's was the first and only band ever to be voted into the number one position both as the best sweet and the best hot orchestra in the country in the 1946 "Down Beat" poll.

And in case you care, though to use it could hardly seem less important. Duke Ellington used the technique of standing at the piano during his stage shows many years before Maurice Rocco and other vertical keyboard technicians thus identified themselves.

This is the record of Ellington's past. Where does he go from here?

Last year, the same "Down Beat" that had accorded him so may poll victories came out with a sensational attack, declaring that Ellington was washed up, that his band was a shambles, and he might as well disband it before it fell apart beneath him.

That it was a sensational attack and that it hurt Duke personally as well as damaging his prestige and bookings, is indisputable; and there have been many times when even the most rabid Ellington fans have felt this way about the Duke.

http://www.leonardfeather.com/feather_ellington.html

(Editor’s note: This was written and published six years before the spectacular Ellington renaissance at Newport!)